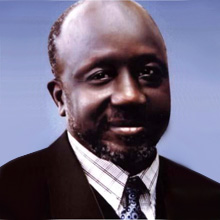

Yousif was born into the Miri tribe, one of more than 50 ethnic Nuba groups. In the days before Sudan's rulers began enforcing an Arab-Islamic identity down the barrel of a gun, his parents were happy to raise him as a Muslim, and gave him an Arab name in preference to that traditionally given to first-born Nuba boys, Kuku. Yousif grew up believing he was an Arab. "If you told me otherwise," he once said, "I would hit you."

All this changed in second- ary school, when his headmaster stopped teaching him, saying: "What is the use of teaching Nuba who are going to work as servants in houses?" "What's a Nuba?" Yousif asked.

He discovered the answer as a political science student at Khartoum University, immersing himself in Nuba history. At the house of a Nuba friend one evening, he was dismayed to hear one child say to another, "You are a good singer. But, unfortunately, you are black." In that moment, he said, "I started to reject assimilation. I said, 'I will build my civilisation, and then I will forgive anyone who humiliated me before.'"

While still at university, he helped create the Komolo, the first political organisation of Nuba youth. In 1981, he was elected to the Kordofan regional assembly, but found himself accused of racism whenever he spoke of the Nuba. Despairing of political change, he joined the SPLA.

For him, liberation meant respect for the rights of all. He sought self-determination in its original sense - for the Nuba to have the right to choose what kind of government they would have, and with whom.

Yousif's years as SPLA governor-commander in the Nuba mountains set new standards of rebel behaviour. He refused to tolerate abuses, and brought some indisciplined soldiers before firing squads. He built a civil ad ministration that was unique to SPLA-controlled areas, and let the Nuba freely choose between resistance and surrender. They voted, overwhelmingly, for resistance.

Yousif was the embodiment of the traditional Nuba values of political and religious tolerance. He fathered a renaissance of Nuba culture, and gave the Nuba a self-confidence that was their strongest weapon when Khartoum declared holy war against them in 1991. Encouraged by him to be self-reliant, the Nuba fought Khartoum's blockade by creating a teachers' training college and a nursing school, despite having almost no educated class.

I n 1993, after two years of famine in which thousands died unseen, Yousif found his way to Europe to seek help for his people. He returned almost empty-handed, disappointed by his first encounter with the west. "We are like a sinking man in the river, and they are standing on the bank shouting encouragement," he said. "We do not fear bullets, but we feel bitter when a lot of people - especially children - die because of malaria."

Told he had prostate cancer 15 months ago, Yousif had one wish - to see a just peace before he died. That was not to be. But it is certain that his existence contributed to independence of South Sudan.

He is survived by his three wives - Fatima, Hanan and Imm Masaar - and 14 children.

Yousif Kuwa Makki, Nuba resistance leader, born August 1945; died March 31 2001